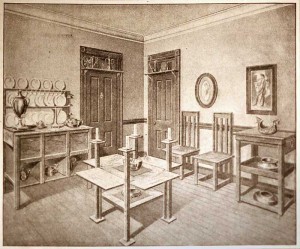

Recently, in the course of preparing an exhibition in Los Angeles, I stumbled across an early 20th century designer and teacher named Louise Brigham. I’d never heard of her, and I’ll bet you haven’t either. She turned up in a hundred-year-old copy of the Ladies’ Home Journal, which probably isn’t high on anyone’s reading list. In it was an article by Brigham entitled “How I Furnished My Entire Flat from Boxes.” The accompanying illustrations showed rooms filled with early-modernist furniture, strikingly more austere than either the conventional furniture designs of the day or the then-avant-garde Mission and Prairie styles being popularized by Gustav Stickley, Frank Lloyd Wright, and others. Brigham was inspired in part by the rectilinear designs of the Austrian architect Josef Hoffmann, but her work has a raw simplicity that won’t surface again until the 1930s, in the ‘crate furniture’ of Gerrit Rietveld.

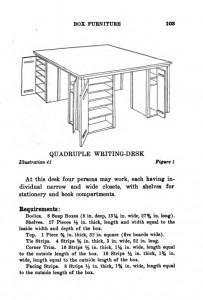

But what really startled me was that all of the furniture was built out of recycled packing crates—the soap boxes, canned-corn boxes, and gelatin boxes that would otherwise have been tossed on a scrap heap. Brigham had, in fact, designed an entire program of such furniture and published a book about it the prior year, entitled Box Furniture. In this book, she gives not only plans for a hundred different pieces of furniture, but also instructions in basic carpentry and color schemes for entire rooms.

Unlike most design in any period, Brigham’s book is aimed squarely at working people of very limited means; her intention was to bring both practical skills and advanced design to those who might otherwise not be able to afford either. She wrote Box Furnitureat a time when the average American worker earned less than $400 a year and a single piece of new furniture could cost a week’s wages. Brigham went on to furnish her own New York apartment almost entirely from box furniture, as a kind of model and advertisement for her system, at a total cost of $4.20.

She also proselytized for her system widely in Europe and the United States, and she built a number of pieces into settlement houses, as she was an active champion of the settlement movement. She founded a workshop for teaching basic box-furniture carpentry to boys (and later girls), the Home Thrift Association; it had its first headquarters in New York’s Gracie Mansion. I was intrigued by what seemed an early appearance in the United States of an ethos of sustainability in design and wondered why I hadn’t heard of Brigham. Perhaps I had come across her and just forgotten? But when I went to google her, I discovered that very little has been written about her since her heyday, apart from a tiny handful of recent articles that argue for her as a pioneer of sustainable and affordable design. She did not even have a Wikipedia page. She does now, because I wrote one for her.

I got so interested in Brigham that I dug out the contemporary newspaper articles on her, and I got a copy of her book (it’s also available as a PDF download from several websites, including Google Scholar). Working from these sources and two fine articles by Larry Weinberg and Jessica M. Pigza, I’ve reconstructed as much of her life as I was able to in a little over a week of digging, but huge gaps remain. I’m working on filling in some of the gaps, because the questions that occurred to me when I first saw Brigham’s work are still unanswered: What kind of person was she? What was her family background? What kind of art education did she get? Why did she not become a professional designer to the well-to-do like her friend Hoffmann? Did her ideas directly influence the De Stijl designers, and if so, how? How did she get involved in the settlement house movement? And most of all: how is it that this visionary spirit has all but disappeared from the historical record?

Louise Brigham's Wikipedia page

Box Furniture received a good deal of initial exposure; it went through several editions and was translated into a number of foreign languages. It is one of the earliest design projects to incorporate the idea of modular or sectional units and to organize an entire program around both social and aesthetic objectives. It is a direct precursor of today’s do-it-yourself and sustainable design movements, as well as of consumer-assembled kit furniture such as Ikea produces. Yet none of Brigham’s work is known to have survived, and her box furniture project is all but unknown today, barely rating a footnote in the canonical story of 20th century furniture design.

The reasons for this erasure deserve closer examination, as part of the larger story of women’s role in the history of art, design, and technology. Right now, there are too many gaps in the story of her life to draw secure conclusions. So I invite anyone who knows something of Brigham to contact me, or to add to her Wikipedia page. And everyone in the Los Angeles area is invited to visit a small exhibition about her work that I’ve created—in tandem with another writer, Ruth Coppens—at the Institute of Cultural Inquiry. Entitled Evidence of Evidence, it will be up until March 30th. (I’ve written a bit about how that exhibition came about here.)

Zinc– What you say about the Arts & Crafts movement, is certainly true– the late 19th century in general is such a transitional period for women, in that they are beginning to get increased access to professional-grade training (through art schools and apprenticeships) but are still largely shut out of the professional world.

I didn’t know about Joshua Tree’s founding. If you have any solid info on this, put it on Wikipedia– the entry on the park has nothing whatsoever about its history!

Zelda, I love this work (and the wikipedia contribution)!

I recall that the Arts and Crafts movement involved many women whose work (e.g. in fabric design) deeply influenced, and sometimes directly undergirded, the output of the “great men” of the movement. And, on another sustainability tangent: the founding of Joshua Tree as a park also has a similar story, right? A woman who was told by the great wilderness guys to go play in the desert …

susie– thanks for the vote of confidence. the pursuit of information on LB continues…

i don’t have an intellectual comment. just writing to say that this is rad. i’m appreciative of the sharing aspect of such lesser known histories via the internet. i hope you might be able to pursue your many interesting questions and offer more insight about ms. brigham.

Lilly– thanks for the lead. Clearly one of the things I need to look at more closely is how LB situated her own work in the realm of the domestic– in relation, say, to Taylorist ideas of efficiency, to the post-Morris idealization of ‘craft’ skills, to that enduring middle-class belief in knowing what is needed to upgrade the lives of ‘the poor’.

Also, I want to get a better handle on LB as functioning under the rubric of ‘teacher’ rather than designer– did this, for example, give her a cover under which it became possible to train boys in a skill (carpentry) that was normally not taught to or by women in her day? (And how did she acquire such skills herself?)

Zelda, this is amazing work. Thanks for posting about this. This reminds me a bit of Keith Murphy’s writing about Swedish feminist Ellen Key’s advocation of “beauty for all.” Key was a 19th century activist who focused on the immediately experienceable domestic realm as a site of (design) politics. She is discussed around page 95 of Murphy’s dissertation (http://gradworks.umi.com/33/46/3346915.html). You should go have a chat with Keith (UCI faculty in anthropology) about Louise. He might have some leads on places to look.