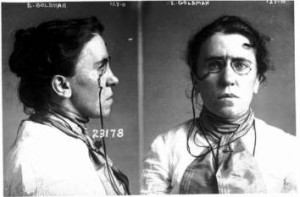

I recently came across this double police mug shot of Emma Goldman over on Slate, in “A Short History of Mug Shots” (I’d guess they cribbed it from this mug shot site). I’ve seen at least one other pair of mug shots of Goldman (below), but I found this one particularly interesting for its semiotic slippages.

As with all such mug shots, the purpose is to construct the subject as a criminal (and in this case also as an undesirable alien). But Goldman’s neat hair and middle-class clothes—especially that great hat—partially block this reading. In Barthian terms, the hat is the punctum of the photograph, the point to which the eye constantly returns even though there is no possible sense in which it was intended as the focal point of the photograph when it was taken. Perhaps that is why the photographer made her take it off for the second shot.

Moreover, the lack of an immediate visible distinction between the two photographs (the vertical line traditional in mug shot pairs) suggests a first reading of not a single person but two sisters, perhaps twins, one more relaxed than the other. One can almost imagine these vivid images gracing a carte de visite. Nor would they necessarily have seemed too ‘serious’ for such a use. The technology of photography at this time was still such that—due to long exposures—everyone looked serious in their photographs.

The other mug shots (at right) do a better job with their criminalizing semiosis: the stripped-off outer clothing, the wild hair, and the more rigid full-face and profile positions. Here, too, the plain background more clearly reads as a police station wall—in the 1893 photos, the impression is rather of an ordinary background out of focus.

Both of these mug shot pairs contrast with by far the bulk of the Goldman photos I’ve ever seen, which are studio portraits typical of the era like the one at left. There are many variations on these—sitting, standing; full-length, bust-length—but a good number feature the ‘thoughtful intellectual’ typology of hand under chin.

I prefer either of the mug shot pairs to these studio portraits—although just as posed and just as formal, they are at the same time much more candid. In those mug shots I can see the determination, self-possession, and anger that must have been major features of Goldman’s character. The studio portraits seem perverse by contrast, offering (especially in the aggregate) a view of a comfortable, stable, middle-class existence that takes almost no account of her actual life.

I’m curious to know if any photographs of Goldman feature in her autobiography; and if so which?

Thanks for posting these. I’ve seen the second photos my entire life, but have never seen the first. Love them so much. I’m halfway through reading her autobiography, Living My Life, and these photos compliment it so well.

I take your point about cosmetic surgery’s ‘normative inversion’ of the body, but I don’t think the problem lies exactly in the requirement to adapt to a technologically created appearance as the new ‘real’. In this sense, cosmetic surgery is like certain other forms of surgery (amputation) as well as accident (scars) and aging that all require us to adapt to a changed physicality. I think the problem lies in the narrowness of cosmetic choices and the way these tend to force the body away from its idiosyncratic physicality. (Hmm, maybe this is what Welton meant– the new real not being the new physical reality but the new conceptual frame?) It’s this that I most appreciate in Orlan’s later surgeries– that they are forging a variant route to difference than the familiar ones listed above.

The question of photographs as proto-avatars is an interesting one. It depends in part on how loosely you want to define agency. I take avatars to have agency not just in the sense of enactment, exerting power, influence etc., but also in the responsive sense of being able to make ad hoc decisions (even if within a very narrow range of choices). I use the term ‘avatars’ more strictly than most people, I think, and reserve ‘toons’ and ‘icons’ for a simpler kind of visual representation. Photographs as semiotic carriers clearly have agency of the first kind (passively creating consequences as they circulate) but not of the second (responsive abilities).

Zelda, love these mug shots as well as your commentary. It reminds me also how fun/ productive it is to roll back the clock by ~100 years or so everytime someone notes the “unprecedented” character of the technological moment we’re living through now. Photography as a technology played out some of the political/philosophical debates that are recycling their ways through “new media” studies.

I’m also reminded, by your post, of the conversations about cosmetic surgery today. Kathryn P. Moran argues that cosmetic surgery is creating a “normative inversion” of attitudes toward the female body: “Cosmetic surgery entails the ultimate envelopment of the lived temporal reality of the human subject by technologically created appearances that are then regarded as “the real” (Welton 1998, 327).

As photographs began to travel, did they also create technological avatars of the person, complete with narratives of their class, race, character, etc? I haven’t seen much historical/critical commentary on tech/ digital avatars that pairs those moments together, as I do see here (implicitly) in your post, paired with your other posts on avatars. proxies, identity performance, etc…